It is October 2013, and Rimiko Yoshinaga is standing behind a podium in Minamata, Japan, gazing at an auditorium packed with world leaders.

Silence descends upon the room as she begins recounting how a mysterious illness had killed her father decades earlier.

Yoshinaga would learn her father was one of thousands of Minamata-area residents poisoned in the 1950s and 1960s by industrial runoff laced with mercury, a neurotoxin.

The leaders listening to her on that sunny day in 2013 were hoping to save others from the same fate. They were in Japan to adopt the Minamata Convention on Mercury, an ambitious global accord to rein in the use of a chemical that had plagued humanity for centuries.

“We went there and could hear the voices of the victims. It was absolutely emotional,” Fernando Lugris, a diplomat who chaired negotiations on the convention, recalled recently. “We hoped that this convention would help many other communities around the world to prevent what happened in Minamata.”

This 10 October marks the 10th anniversary of the adoption of the Minamata Convention, a deal that has been hailed as a triumph of international diplomacy. Some 147 parties have ratified the agreement, which calls for countries to phase out mercury use in products, ban the opening of new mercury mines and limit the emission of mercury into the environment.

“The Minamata Convention is such a significant global agreement for people [and] the planet,” says Monika Stankiewicz, the Executive Secretary of the Minamata Convention Secretariat. “Mercury use is not essential. As we move forward to make mercury history, I hope to see more countries joining the Minamata Convention.”

The convention is hosted by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), which has for nearly three decades worked to limit the fallout from mercury pollution.

“We at UNEP are proud to host the Secretariat for this Convention, which protects the environment and human health, including that of small-scale gold miners and children, from the pernicious impacts of this dangerous neurotoxin,” says UNEP Executive Director Inger Andersen.

As the convention enters its second decade, experts are buoyed by the progress of recent years. The trade in mercury has slowed, manufacturers have begun finding alternatives to mercury in a range of products, and public awareness about the dangers of mercury has grown.

But observers caution that much remains to be done before mercury pollution is consigned to the past. In 2019, 2 million people died as a result of chemical pollution, with experts saying many of those fatalities were linked to mercury.

Mercury’s toxic tail

Humans have used mercury for thousands of years; it has cropped up in the historical record everywhere, from Egypt to China. Today, the chemical is present in myriad household products, including some batteries, thermometers, light bulbs and cosmetics.

Burning coal, including for power, is a major source of mercury. Atmospheric mercury concentrations have increased to about 450 per cent above natural levels. The chemical is also commonly used in small-scale gold mining, an industry that globally employs up to 20 million people, including many women and children.

Despite its widespread use, mercury has been known for centuries to be toxic. Exposure can cause a range of serious health problems, including irreversible brain damage. But much of the world would not begin to take the problem of mercury pollution seriously until the slow-motion disaster that engulfed Minamata.

From 1932 to 1968, a chemical factory in the coastal city discharged liquid containing high concentrations of methylmercury, a type of mercury, into a local bay.

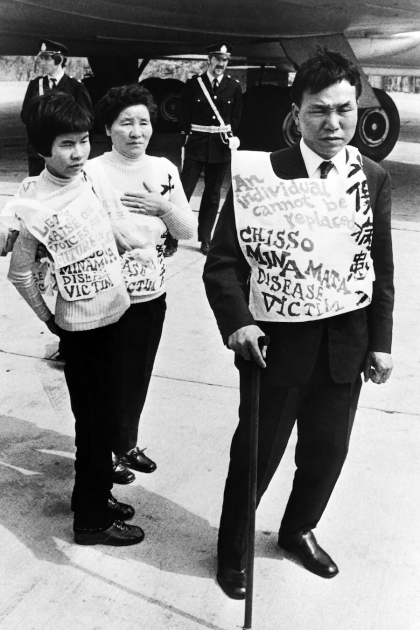

Unbeknownst to residents, the chemical would accumulate in the fish they ate for decades. In 1956, the first human case of what would be called Minamata Disease was recorded. Thousands more would suffer from brain damage, paralysis, incoherent speech, delirium and more in the coming decades. Cats, crows, fish and other species also exhibited symptoms.

“Currently, 70,000 victims have been confirmed in the Minamata area, but it has become clear that the number is more widespread,” says Yoichi Tani, a spokesperson for the Minamata Disease Victims Mutual Aid Association, which has been campaigning for compensation for victims since 1970.

“The damage has continued to be underestimated.”

While Minamata came to symbolize the dangers of mercury, countries around the world, including developing nations, have long struggled with its toxic fallout.

Momentum builds

In 1995, amid mounting concerns about the proliferation of toxic chemicals, UNEP called for urgent action on a range of pollutants. Six years later, under the organization’s guidance, the world signed the Stockholm Convention, a global pact to eliminate or restrict scores of harmful chemicals, including pesticides and mercury.

This would lay the foundation for a UNEP push to bring the issue of mercury to the global stage. To highlight the problem, UNEP created the world’s first global mercury assessment in 2002. It found that almost no corner of the Earth was untouched by mercury – it was even detected in the Arctic – and that the element was building up in fish stocks around the world. (The study has been updated numerous times, most recently in 2018).

“The 2002 assessment ground all the discussions in science and data,” says Stankiewicz. “It was truly pivotal and allowed negotiators to immediately understand what the text of a convention needed to cover.”

Scientific evidence and political will continued to build in the years to come, and in 2009, UNEP’s Governing Council tasked Lugris with negotiating the Minamata Convention through a series of five international sessions.

“There were many people saying it is impossible,” Lugris recalls. “Mercury is almost everywhere, and humankind has been using mercury since ancient times. We’ve known since that moment how dangerous it is, and we have never taken measures before. But we were convinced we could do it.”

While the Minamata Convention would be adopted in 2013, much work remained.

The next step

In the years since, UNEP and the Minamata Convention have helped countries identify the risks associated with mercury and supported strong policymaking to reduce its use. A convention-specific funding mechanism, for example, has provided 24 grants to help parties implement the accord.

UNEP has spearheaded the Global Mercury Partnership, which brings together close to 250 governments, intergovernmental and non-governmental organizations, industry and academia to support the convention’s implementation.

UNEP also participates in the planetGOLD programme, an effort led by the Global Environment Facility that aims to end the use of mercury in small-scale gold mining, an industry that generates US$30 billion annually. The programme works in 23 developing countries.

The Minamata Convention on Mercury is a very important treaty to prevent the spread of mercury damage. However, the activities have only just begun,” says Tani, the spokesperson for the Minamata Disease Victims Mutual Aid Association. “There are many issues that need to be addressed.”

On 30 October, leaders will gather in Geneva, Switzerland, for the fifth Conference of the Parties to the Minamata Convention, an international gathering that aims to continue refining the agreement. The agenda includes discussions on thorny issues, including how to reduce the use of mercury in small-scale gold mining. Delegates are also expected to discuss new restrictions on mercury-added products, examine limits for mercury in waste and explore how to improve national reporting on mercury pollution. Those will come alongside talks on the convention’s dedicated funding mechanism, which provides technical assistance to countries.

Ahead of the meeting, experts are hopeful countries can make real headway on issues like those.

Andersen calls on countries to “redouble” their efforts in Geneva. “Stepping up action on mercury is essential to protect human health and the environment from mercury pollution and help attain a pollution-free planet,” she says.

Lugris – now the Ambassador of Uruguay to China – hopes the trailblazing “Minamata spirit” remains strong among negotiators.

“The Minamata family has been always a bit different from other families. We have always continued to be very progressive,” Lugris says. “If that spirit prevails, I am sure that we can continue to make a lot of progress.”

This blog was originally published by UNEP